Bit of a cheat post this one, but Boydell and Brewer have recently published an interview they conducted with me on my book, Birds in Medieval English Poetry, so thought I’d share it. Click here, or simply read the text below.

Thank you for assisting our discussion of your book, Dr Warren. To begin, could you tell us a little about how you came to write this book, which is now the second in our new series Nature and Environment in the Middle Ages. What first drew you to the natural world in literature?

When I decided to return to medieval studies after some years in teaching, it was an obvious choice for me to pursue a subject that combined a personal love of mine with literature. I knew that there was plenty to say about birds, in fact, because I’d written on this subject for my undergraduate dissertation a number of years before. Medieval literature is full of birds, and it seemed strange to me that no one had yet produced a full study examining how they are represented and what their significance is, or at least not one that seriously considered the presence and relevance of ornithological interests, rather than simply birds’ totemic aspects. Birds—as just one, conspicuous set of species in the natural world—were clearly of profound interest to medieval thinkers and writers, and I wanted to explore how and why. So that’s how it all began, but the project inevitably took on much bigger proportions for me as it progressed.

Do animals receive enough attention in medieval scholarship?

I think it’s more a question of do they receive the right sort of attention. Animals haven’t been ignored in medieval scholarship, but there is a long tradition of thinking that medieval poets weren’t really interested in actual species themselves; it was what they meant that was important. Birds, specifically, have always received short shrift in ornithological histories, which tend to deal with Aristotle, and then skip to the 16th century. The medieval chapter in these histories is always by far and away the shortest—it’s a respectful nod to the more familiar textual references that exist, and which suggest that birds must have been observed on some level, but the popular attitude, at least, is that medieval people ‘knew little about birds, and cared even less’ (Stephen Moss, A Bird in a Bush: A Social History of Birdwatching).

With the spike in 21st century ecological sensibilities, though, there has been a revolution right across disciplines. Ecocriticism and animal studies have achieved considerable popularity and influence in medieval scholarship over the last decade, striving to emphasise the reality of nonhuman creatures in life and text, and demonstrate that how medieval people thought about the natural world and their relationship to it was much more complex and diverse than we have previously thought. So yes, I do think animals are receiving the right sort of attention in medieval scholarship now, but there’s still some way to go (if you look at how many panels there on nonhuman topics at the big medieval congresses each year in Kalamazoo and Leeds compared to other more traditional topics, there is a very striking disparity).

Your book discusses a rich span of poetry, from Anglo Saxon texts through to Chaucer and Gower. Do you have a favourite?

I do have a particular fondness for The Seafarer. There’s something about the early Christian asceticism and the tempestuous seascape in which this plays out that really appeals to me; I suppose it chimes with my love of bleak, people-less spaces, like marshes. There is something so affecting and powerful about the intimate linking of the exile and the wild nonhuman, and the fact that birds are a conspicuous part of the environment and the Seafarer’s experience is fascinating to me. Seabirds are especially compelling to us humans I think, being that that they are perfectly at home in a location so alien and hostile to us—their mysterious experience is what, paradoxically, makes them such rich metaphors. I’m sure this must have genuinely been the case for those monastics seeking solitude and hardship on remote Atlantic islands like Skellig. If you’ve ever visited locations like this you’ll know you just can’t avoid the raucous presence of seabirds!

How did you come to settle on this particular selection? Did you have many to choose from?

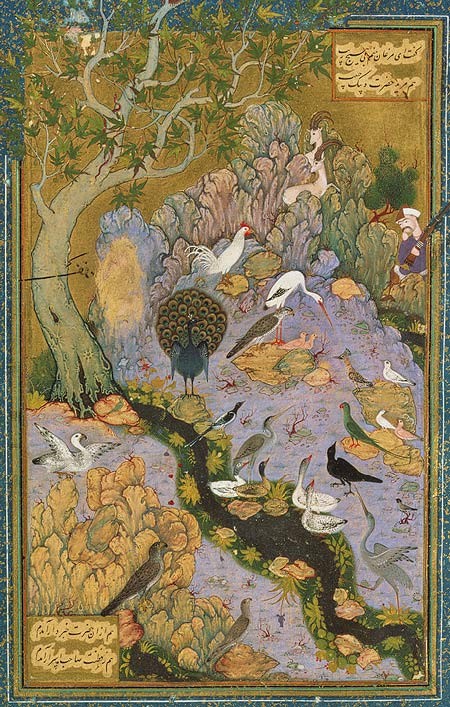

There are so many texts to choose from, especially if you move outside European traditions and consider, e.g., Arabic or Persian texts as well. I chose only English texts because I was interested in representations of native British wild birds, and because I purposefully wanted to bring new perspectives to much-studied poems by revealing and exploring their intricate and knowledgeable depictions of birds. These birds have received attention before now, but I wanted to take this further—to look at how the ornithological elements might be part of the wider thematic interests of the texts. There is also a subsidiary thread to the book which seeks to fill in some of those gaps about medieval ornithological knowledge, for which it was useful to survey the whole span of the Middle Ages.

What place, if any, did birds hold in the everyday lives of people in the Middle Ages?

As for the everyday lives of most people, it’s very hard to know. The surviving texts of the medieval age, of course, were not written by or for, and can’t be said to represent the ‘everyday lives’ of, most people. But the written evidence does imply that for intellectual or elite milieux, at least, birds had a diverse and important status in all sorts of ways ranging from the practical to the philosophical: food, quills, hunters (and quarry) in falconry, caged songbirds, intriguing comparative subjects in theories about voice and music, allegories in bestiaries, subjects of ‘special mention’ in encyclopaedias (Bartholomew the Englishmen). In poetry, of course, birds became elevated metaphors for a whole variety of subjects, but what I aim to do in the book is show how knowledge of real birds and species (the ‘everyday’ if you like) still important in informing how these metaphors work.

Beyond this, though, it is possible to get a feel for how birds must have played a part in vernacular lore and discourses. Old English names for birds, for instance, suggest remarkable degrees of observation and listening, and their presence in Anglo-Saxon place names or charter boundaries conveys how they were acknowledged as important elements of environment (‘take the path left past the pond where the coal tit lives’, sort of thing), and there is no reason to believe that much of this didn’t descend from or wasn’t shared by your ordinary man and woman living and working in the natural world where birds are. There is no doubt that wild birds generally were much more plentiful in the Middle Ages; our modern ‘baseline’ perception is heavily distorted because we live in a world where pretty much all species, but particularly groups like farmland birds, have dramatically declined due to modern industrial practices.

Expanding on the last question, why would the presence of birds in poetry have appealed to a medieval poet or audience?

Beyond what I’ve suggested above, I think the overall thing for me is that birds are such consummate and enigmatic transformers. They complicate, escape and thwart human attempts to categorise—something I pick up on with particular reference to the Exeter Book Riddles in the book. Birds, in life and in poetry, always seems to be in some sort of ‘trans’ status and I think this has a lot to do with why they were (and are) so compelling. David Wallace has eloquently said in his recent book on Chaucer that medieval conceptions of the human condition engaged the ‘perilous art’ of aligning ‘bawdy bodies and stargazing intelligences’. From this perspective, it’s not hard to see why birds were illuminating parallels—they are animals below human status in one sense, and yet occupy the ethereal heights above humans as well; they are both mundane and numinous at once.

A captivating aspect of your volume is the depiction of everyday birds and how their reality is used and transformed into metaphor. What’s your favourite example?

Again, I’m drawn to the alien, pelagic qualities of the seabirds in The Seafarer which the poet aligns with the solitary speaker, but perhaps one of the most interesting examples is the owl in The Owl and the Nightingale. Part of the poem’s sophisticated comedy, for me, is that the ‘realities’ of the eponymous birds are consistently (and knowingly, on the part of the author) confused, which causes problems when these particular qualities are transposed into metaphorical use in texts like the popular bestiaries. So, when the nightingale attacks the owl’s day-blindness (which becomes a well-known metaphor for the sinner who cannot or refuses to see the light of Christ), we are aware that profound moral ‘truths’ are being drawn up on false premises: the owl states herself in the poem that this particular ‘truth’ about owls is just plain wrong.

This book clearly demonstrates a real love for birds. Are you an avid birder yourself?

I certainly am. I birdwatch a lot in Kent where I live, particularly on the marshes up in the north of the county. It was my uncle who got me into birding when I was very young, and it’s his photos, in fact, that illustrate the book, including the striking image of flying godwits on the front cover.

Of course, you don’t need to be a birdwatcher to write about birds in medieval poetry, but I do think it has helped attune me to various nuances, such as the importance of sound or accurate observation in Old English bird names, or the ornithological aspects of certain species that clash with allegorical treatments.

What are you working on now, or will you be working on next?

Still birds! I was approached by a publisher some years back whilst writing my PhD about the possibility of producing a trade version of my thesis. So, now the monograph is finished up, I’m turning my attention to this new project. It will take some of the informative, ornithological elements of the monograph and weave these into a nature/travel-writing narrative. The first chapter is set on the Essex Marshes, particularly concerning a place called Foulness Island, to explore Old English place names, and how birds, but also the natural world more generally, are intimately observed and become a part of human conceptions of place.