The last decade has seen a surge of ornithological interest in the complexities and mysteries of bird songs and calls. It’s been known for some time that certain species have remarkable mimic abilities (like the marsh warbler who intentionally weaves other species’ songs into its own repertoire, or the incredible lyre bird who can imitate just about any sound on the planet), but more recently birds’ voices have also played a major part in identifying new or split species (two species so alike that formerly they have been considered one, or subspecies of one). The popular Sound Approach project has demonstrated the need for taxonomic re-categorisation amongst certain Eurasian owls, for instance, and even the discovery of a completely new species. As recently as 2014, a bird heard in China led to a whole new avian family. There is no doubt that modern technological advancements are critical to all this new research. As much as we do know, this science wizardry also reminds us that where nonhuman communications are concerned, we barely know anything.

In essence though, all of this focus on bird sound is nothing new. Various classical authors were already clued into the virtuosity and intricate meaning of birds’ voices. One of the most famous examples is Pliny the Elder’s (1st century AD) ornate description of the nightingale’s song in his Natural History, which employs the terminology of skilled musicianship to convey the bird’s brilliance:

[T]hen there is the consummate knowledge of music in a single bird: the sound is given out with modulations, and now is drawn out into a long note with one continuous breath, now varied by managing the breath, now made staccato by checking it, or linked together by prolonging it, or carried on by holding it back; or it is suddenly lowered, and at times sinks into a mere murmur, loud, low, bass, treble, with trills, with long notes, modulated when this seems good – soprano, mezzo, baritone; and briefly all the devices in that tiny throat which human science has devised with all the elaborate mechanism of the flute. (10:43)

There is obviously an element of poetic conceit in this, but Pliny uses the language of human music to attempt describing something as intricate and complex in its own way (listen here, and just for fun, try here to translate any word into nightingale ‘speak’!)

A Roman nightingale, from Pompeii – the same century as Pliny and Plutarch were writing (Source: British Museum)

Our modern knowledge, too, of the learning and teaching abilities of birds – like the fairy wren that teaches its unborn chicks a food ‘code’ to deal with cuckoo impostors – was pre-empted by the ancients:

As for starlings and crows and parrots which learn to talk and afford their teachers so malleable and imitative a vocal current to train and discipline, they seem to me to be champions and advocates of the other animals in their ability to learn, instructing us in some measure that they too are endowed with both rational utterance and with articulate voice … Now since there is more reason in teaching than in learning, we must yield assent to Aristotle when he says that animals do teach: a nightingale, in fact, has been observed instructing her young how to sing. (Plutarch, On the Intelligence of Animals)

Despite these minority voices that recognised the innate and intended meaning of bird vocalisations, the prevailing attitude systematically divided human and nonhuman voices – the first was rational and the second nothing more than instinctive repetition. This was the customary philosophy that led into and endured throughout the Christianised Middle Ages, and the rational/irrational adage became common place. So Saint Augustine remarked that ‘either one would say that magpies, parrots, and crows are rational animals, or you have recklessly named imitation an art’ (On Music), and centuries later the Flemish theologian Thomas de Cantimpré could still state simply and with conviction that ‘the human voice is articulate, and animal inarticulate’ (Liber de natura rerum, I.xxvi).

However, as in the classical period, there were more free-thinking writers that spoke out for misrepresented nonhuman voices. It is quite clear from Old English glossaries that at least some Anglo-Saxon people were competent listeners. A large number of species are not named according to their appearance, as is the modern preference, but rather according to their song or call. And so we have, to name just a handful: hrafn (raven); ceo (chough); finc (finch – the typical ‘pink pink’ sound of a chaffinch); maew (gull); rardumle (bittern – ‘reedboomer’); stangella (usually thought to be a name for kestrel – ‘stone-yeller’); nihtegale (nightingale); cran (Isidore of Seville, a 7th century bishop, wrote in his Etymologies that the crane in Latin (grus) is named for its trumpeting call).

Perhaps more interesting, though, are those moments where writers are forced to admit, willingly or otherwise, that translating nonhuman sounds isn’t always straightforward, and sometimes is just darned impossible. In Aldhelm’s Rules of Metre (7th century), for example, a teacher attempting to give the utterances of all sorts of nonhuman beings to his student is forced to say that storks … well, ‘make a stork noise’ and ‘kites make kite noises’. To Aldhelm, of course, this would only prove his point – that these are irrational voices, but it also inadvertently exposes the gulf between different modes of expression and their meanings. To quote another classical author: ‘even if we do not understand the utterances of the so-called irrational animals, still it is not improbable that they converse’ (Sextus Empiricus, Outlines of Pyrrhonism, I.73-6). In moments like these, the limitations of human languages are clear too – they cannot adequately cross boundaries.

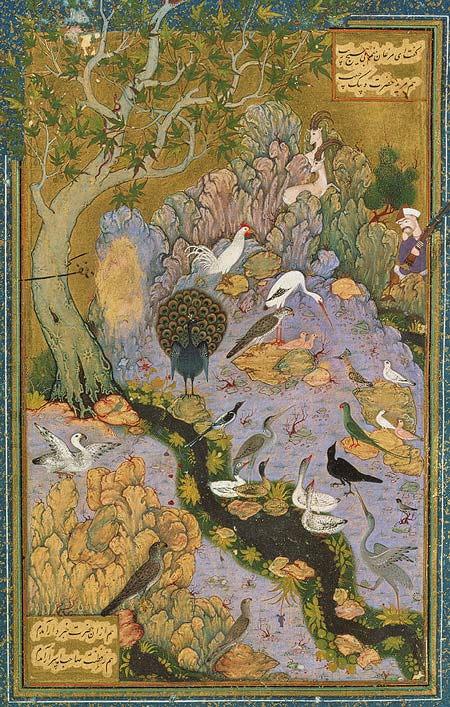

Problems with translation become a key issue in a well-known late medieval Chaucer poem. The Parliament of Fowls is a dream vision bird debate poem – a popular form at the time in which two or more birds representing human individuals or perspectives conduct a formal argument as witnessed by a human narrator in a dream. In this case, the topic is love (or breeding), and Chaucer creates a great deal of humour by allowing the assembly to fall into chaos because the lowly birds (worm and seed eaters) disagree with the lofty pretensions of the birds of prey who want to conduct themselves according to the rules of courtly love. For certain birds, like the goose and the duck, this is all too much – why on earth would you spend time pining after an unrequited love when there are so many others to choose from?! Just get on and pick a mate! In Chaucer’s poem, that is, birds fail to consistently represent human beings; they keep on doing and saying birdy things.

A quecking duck in the Gorleston Psalter, 1310-1324 (Source: British Library)

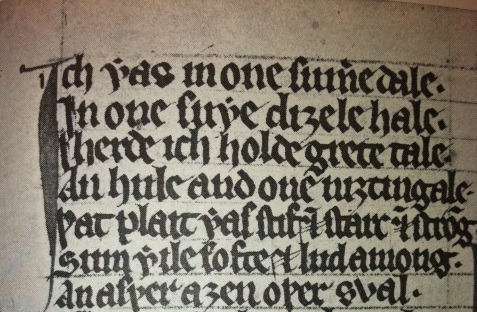

The moment in the poem that has preoccupied me over the last year (for the full extent, see here) concerns these birds:

The goos, the cokkow, and the doke also

So cryede, “Kek kek! kokkow! quek quek!” hye,

That thourgh myne eres the noyse wente tho.

The goose, the cuckoo, and the duck also

Cried, ‘Kek kek! kokkow! quek quek!’ so loudly

That the noise went then right through my ears.

(498-500)

What is strange about line 499 is that it is the one and only instance of phonetically-rendered bird call in the entire debate. Elsewhere, as is conventionally the case, birds speak a human language (or rather, they never actually speak in their own language – the voice is human from the start, only inserted into bird bodies). What then are we to make of a line that has the birds momentarily cry out in a transcription that, like the quacking duck in the marginal illustration above, at least seems to represent genuine birds’ vocalisations?

In my view, when the birds stop talking English and suddenly speak out in a strange semiotic mode, Chaucer is playing with the same sorts of curiosities that turn up in that sound wordlist from Aldhelm – there is a fault in the transmission. It raises all sorts of interesting questions concerning translation between species in the poem: are we to imagine that the line stands as his attempt to translate what he denounces as irrational ‘noyse’ elsewhere? In which case, why does he not do so in Middle English as at all other times in the debate? Are we to understand, maybe, that the dream enables the fantasy of nonhuman to human understanding, and that the birds do not actually speak English to each other? Or perhaps the birds’ utterances indicate something incomprehensible to the narrator – accurately reported, anomalous bird sounds amongst voices that otherwise genuinely speak English? The line, in fact, is doubly complex because it both conveys real bird calls, and presents a human mimicking bird calls (exactly like modern ornithologist’s attempts to replicate bird calls). And, given that the debate actually takes place between a multitude of birds, to what extent are other species meant to understand ‘quek[s]’ and ‘kek[s]’ – can they translate too?

More profoundly, Chaucer’s bird call line, interrupting the human speech, invites us to bridge the communicative gap. It provokes a speculative translation act from us at this moment, a playful invitation to imagine what the birds mean (or perhaps fail to mean) amongst their own and other species. From this angle, the lively vernacular of the goose and duck at other times conducted in English (‘All this is not worth a fly!’; ‘Come off!’) is an attempt to translate this otherness of bird species, and that of all nature’s voices. As a modern ornithologist states in a recent article on birdsong, ‘We will probably never be able to talk to birds, but we may yet be able to know what they are saying’ (David Callahan, Birdwatch, May 2016). Chaucer might have been dubious about such confidence, but I think he’d be happy to admit that ‘queck’ is far from meaningless.